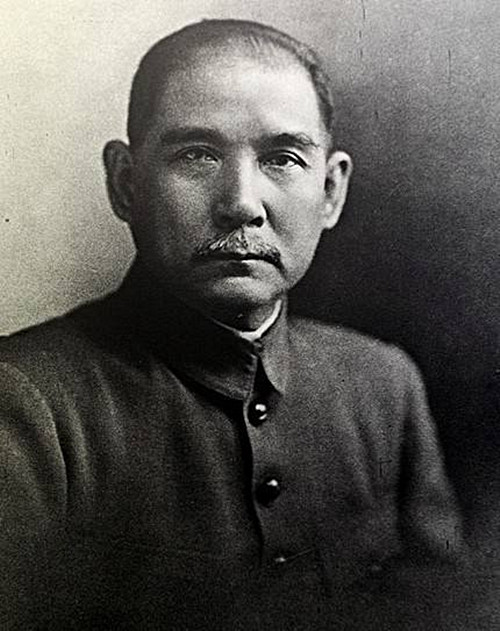

The Mao Suit, as it is known in the West, is known to the Chinese people themselves as the Zhongshan Suit, after Dr. Sun Zhongshan, better known in the West as Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (1866-1925), the Chinese revolutionary and political hero of late- and post-Qing (CE 1644-1911) Dynasty fame. Dr. Sun was the leader of the revolutionary movement that was instrumental in bringing down the Qing government, which it replaced with the Republic of China (1912-1949), ending China’s 2000 year old Imperial era. Dr. Sun also served as the first head of the Republic of China, and continued as its military leader.

The Mao Suit (since this is written for an international audience, we will stick with the name by which the suit is best recognized, no disrespect meant to Dr. Sun) has more generally been referred to as the Chinese Tunic Suit. The following brief history of the origins of the Mao Suit is therefore in order.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ORIGINS OF THE MAO SUIT

Though the Mao Suit is credited to Dr. Sun, it was inevitable that a new type of military suit, or dress uniform – which would replace the existing, all-purpose Manchu uniform, whose tunic was called the changshan (“long shirt”) – was in the offing, so whether it was precisely the unform developed with the assistance of Dr. Sun or another, perhaps similar uniform, is not all that interesting, the interesting part being that China, as a country and a nation, was ‘on the move’, and the impetus for this was twofold.

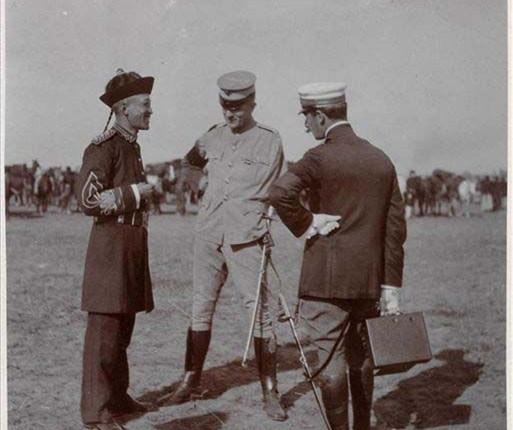

The first and primary influence came from outside, in the form of increasing foreign commerce between China and the outside world (and, indeed, the so-called Unequal Treaties had given many of these foreign powers both trade and territorial concessions in China, the most prominent among these territorial concessions being Hong Kong, which had been leased to Great Britain for 99 years).

The other main influence on developing an alternative Chinese military dress uniform was the increasing unrest among China’s ethnic Han majority group, who were becoming increasingly discontented with the Manchu government of the Qing Dynasty in general, and, in particular, with China’s direct humiliation at the hands of foreign powers (viz. the Unequal Treaties) as well as China’s indirect humiliation in practically every field of human endeavor, especially in the field of science, so replacing the traditional Manchu “changshan uniform” with a Han Chinese military uniform was a way of registering this discontent.

Toward the end of the 19th century, styles of Chinese dress – as was the case for styles of just about everything Chinese, from food to furniture – were coming under foreign influence, where the new Chinese style incorporated elements of Western and other styles, such as Japanese style, with traditional Chinese style. This tendency had long been underway when Dr. Sun decided to revamp the militay suit so as to incorporate some of the features of foreign military dress.

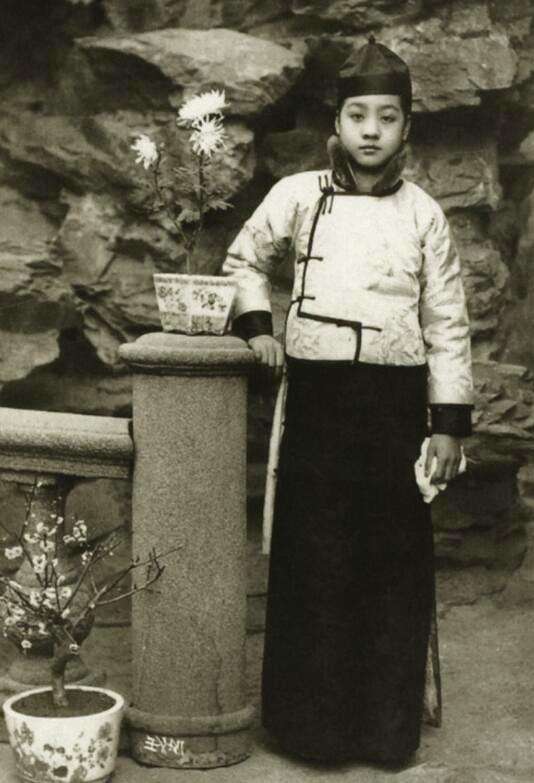

One of the first foreign influences was the addition of a hat (the “hat” in question was actually a sort of cloth or silk cap) to the changshan, which was worn over a robe that covered the body from the waist down. The changshan was a simply designed, front-buttoned garment that extended no farther than to the waist. It was in every respect utterly simple in design, resembling what today one might call a pajama top, albeit, a particularly nicely made pajama top, often of silk.

The Mao Suit that was developed at the end of the 19th century bore the stamp of both Western and Japanese influence: the tunic, or jacket, was essentially a Japanese cadet uniform designed to suit Chinese tastes, while the trousers – and recalling that trousers were alien to Chinese tradition at this time, as the “changshan uniform” mentioned above bears witness – were an adaptation of Western trousers. The jacket of the Mao Suit is actually a quite modest affair, not a great leap forward in comparison to the changshan, except for the pockets.

The Western tradition with dress jackets was to conceal the pockets, except for the flap which covered the opening at the top. Had Dr. Sun opted for this type of pocket, his new tunic would not have looked markedly different from the changshan, therefore Dr. Sun opted for external pockets, or what one calls “cargo pockets” in the U.S., i.e., the entire pocket sits atop the surface of the jacket, save the back side, meaning that the cargo pocket consists of five surfaces – top, bottom, left and right sides, and front – that are sewn to the garment, the sixth and final surface.

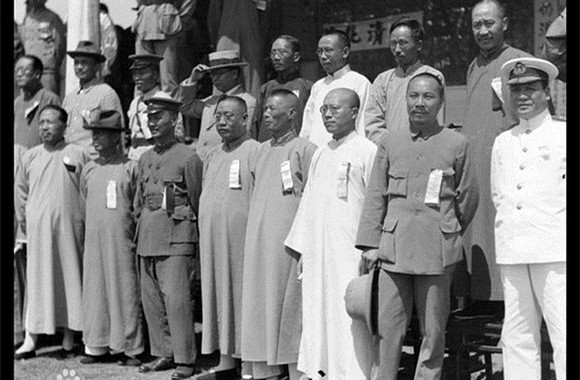

The top flap of the Mao Suit tunic’s cargo pocket was held down by a centered button, just as similar pocket flaps are secured today (though some are secured by snaps today, others by velcro). The Mao Suit tunic originally had 7 buttons down the front, but this was later reduced to only 5. The difference seems to be in the fact that the original jacket was buttoned farther down than was practical, therefore the two lower buttons were eventually eliminated, making sitting considerably easier. In addition, the arrangement of the pockets, with two large pockets below and two smaller pockets on the chest, and with matching right and left sides, gave a two-dimensional balance and a pleasing sense of symmetry to the jacket, which had a short, fold-down collar (almost like a button-down collar but without the buttons) that was devoid of pointed ends – it was cut so as to stand up, and was probably worn starched in order to strengthen this effect.

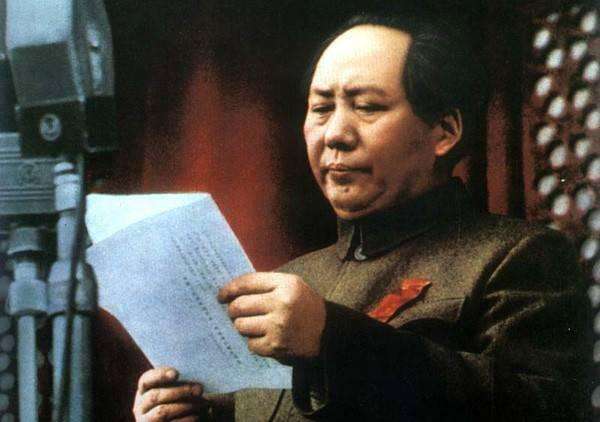

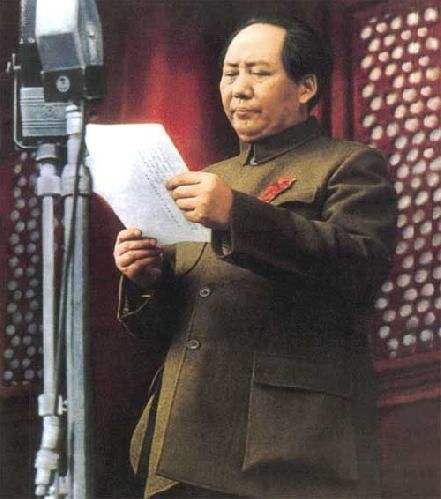

The Mao Suit tunic (trousers are hardly worth mentioning in any suit, as the focus is almost always on the jacket) was in its own way simple yet elegant. It is no wonder, then, that China’s Communists Party later adopted it as their formal military dress during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) – which embraced WWII in the Pacific theatre – when the Nationalists, under Chiang Kai-shek, made an alliance with the Communists in order to better repulse the Japanese invaders. In fact, as we now know, it was a young, future Communist leader, Mao Zedung, who would make the Zhongshan Suit of Dr. Sun Yat-sen famous the world over.

During the period when “Chairman Mao”, as he was best known in the West, held sway in China, the Mao Suit was wildly popular among Chinese males of all ages, even toddlers. This tradition continued long after Mao Zedung passed away, but after China opened up to the outside world under the guidance of Deng Xiaoping, Western influence again began to gain a foothold in China, the result of which is that the Mao Suit is perhaps more popular beyond China’s borders today than within them. But I wouldn’t write off the Mao Suit tunic just yet, as someone somewhere will surely re-introduce it in an updated version, and take the fashion world by storm.

Leave a Reply